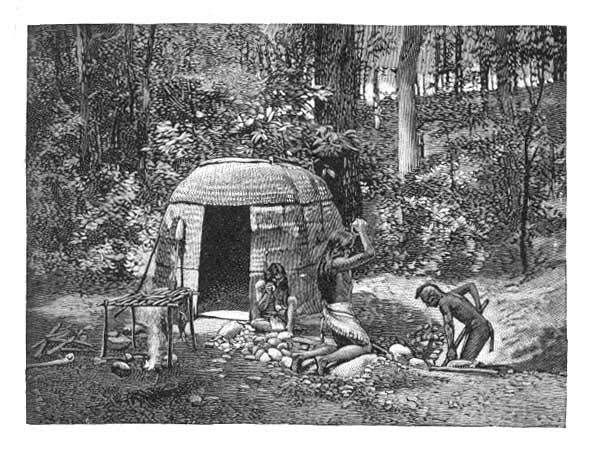

( Wampanoag home block cut image courtesy of http://i157.photobucket.com/albums/t45/maggie6138/nativehouse.jpg )

James Rasmussen [ director of the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center] was matter-of-fact... when asked how he plans to celebrate Thanksgiving.

"Just like anybody else," he said.

But he knew the question implied more, because he is a member of the Duwamish, and he was helping build the tribe's new longhouse in West Seattle.

After all, Thanksgiving may be a day for turkey and football for many, but it marks the beginning of the end and more than a twinge of betrayal for early Native Americans who helped the Pilgrims survive.

Rasmussen knew there was a political facet to the question, he said. "But on the scale of things that bother me, like (the Duwamish) not being federally recognized, Thanksgiving is pretty low on the list."

Certainly, there will be some Native Americans who boycott the holiday, as Elliott Wolfe, a descendant of the Sioux and Chippewa tribes, said he once considered.

He was in high school and was trying to learn about his heritage.

"I started looking into the history and the negative stuff. You learn how much back stabbing there was, and you hear about all the horrible, horrible things that happened, and it just got a little depressing," said Wolfe, now a junior studying construction management at the University of Washington.

But he went to Thanksgiving dinner that year anyway. "Just because I felt bitter about the holiday didn't mean I wanted to ruin it for everybody."

For all the negative associations, Wolfe and other Native Americans say they've forged their own memories and their own meaning for Thanksgiving -- and none of it has to do with Pilgrims.

"We usually go to my aunt's house or my parents' house," he said. "We all get together and share stories. Me and my cousins usually get into mischief. We have a big dinner. There's so many of us, we can't fit at any one table."

Wolfe said: "I think for most American Indians, it's just a time to spend with family. But you have that thought in the back of your mind. You like getting together but you almost wish there was another reason."

There was another reason to go to the dinner -- at some point, he had to move on or be lost in bitterness. Eventually, he stopped being part of a study group with other Native American students.

"I was catching myself with pessimistic attitudes and negative thoughts. There was nothing I could do about mainstream society whitewashing the history. I could complain about how technically my family should own hundreds of acres in the Midwest. But I could get a good job and buy some of that land back."

But although Native Americans have tried to find meaning in Thanksgiving, the day and the way it's taught in schools still can be a sore spot...

Marty Bluewater, executive director of the United Indians for All Tribes, which offers social services and runs the Native American Daybreak Star Cultural Center in Discovery Park... said United Indians tries to focus on the broader idea of Thanksgiving: sharing...

On Thanksgiving, Bluewater, who is Shawnee and Choctaw, will be with his mother and his nephews. They will barbecue a turkey. And they'll say a few Native prayers. "I'll try to take the good parts and make it a time for sharing," he said.

---------------------------

Further resources:

Teaching About Thanksgiving

http://ehighlights.hsd401.org/node/282